Research as a career

For most of my undergraduate life, I was thinking of doing a PhD or some other form of research, so I ended up spending a lot of time finding out about it. If you're also interested in doing something similar, I hope my findings help.

What is research?

The research process is, briefly:

- You find a problem

- Find a solution in the literature/think of something from first principles

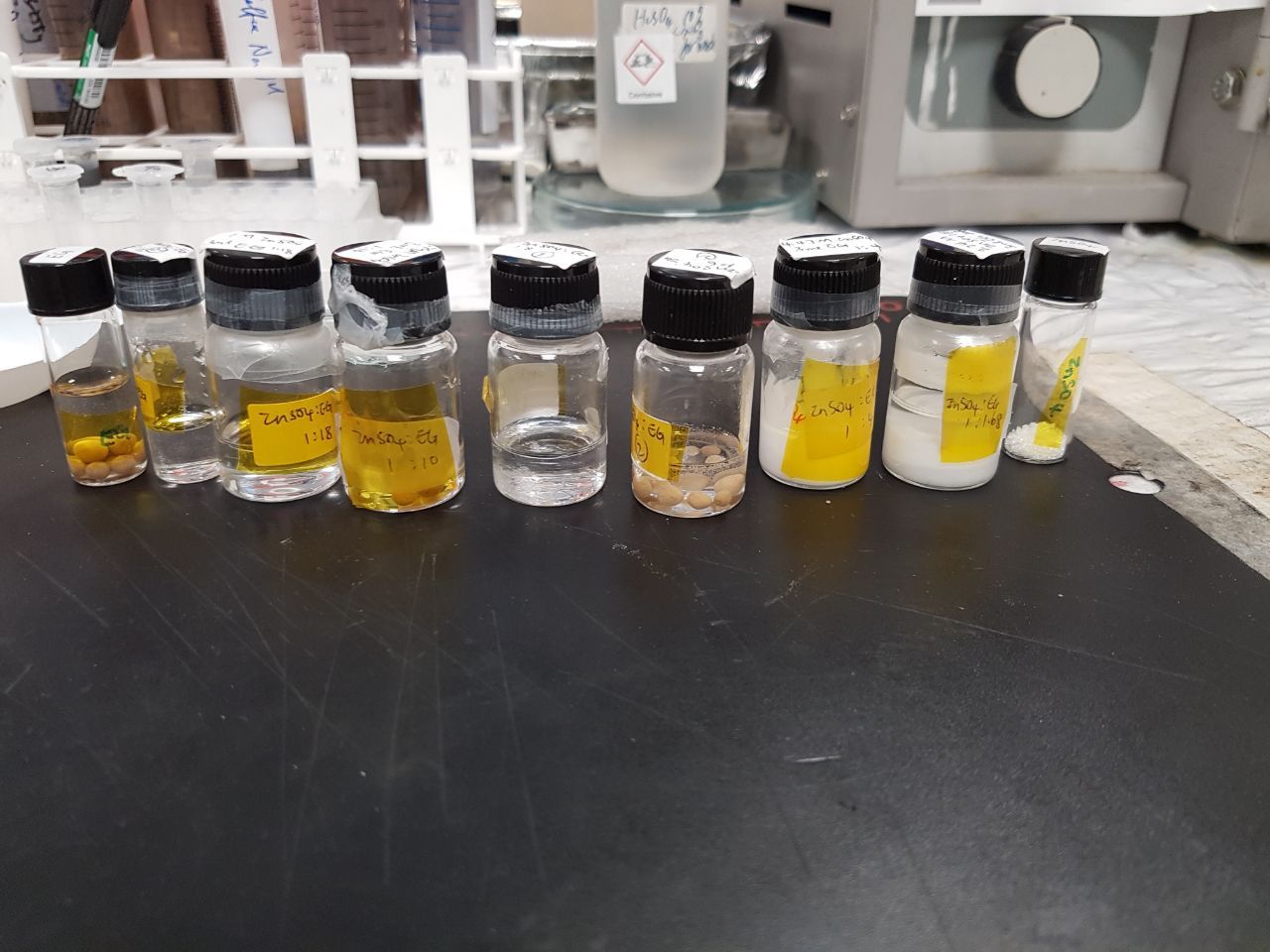

- Try out your idea - run the experiment (takes 2-3 days)

- Log results, analyse them and repeat.

Why academic research?

A research career is good for people who want to solve technical problems. It is also good for people who are sure that the root cause of the problem they want to solve is a lack of knowledge in the area, and not something like policy or collective bad decisions.

Instead of solving a particular problem, it's also good if you're inherently interested in the subject matter. If you'd study this on your own outside of paid work, you might want to consider a PhD in the field. For example, people who would read physics papers for fun might be suited to do fundamental physics research.

If you like working on long-term projects and have the patience for it, it'll be a good fit for you as well.

What topic should you research?

There are a few ways to go about picking a topic:

- Your interest. What subjects were you interested in previously? What research is there to do in fields relevant to your major (if you've already picked one)? What causes do you care about?

- You could scroll around places like ScienceDirect to get a sense of what people are working on, and read a couple of the relevant papers/abstracts. You can also look around major news websites for articles written about new research done in your field.

- There are some high-impact topics listed on Effective Thesis and you can see if you'd be interested in any of those. There are specific topics listed there that would be similar in scope to a final year project, capstone, or thesis.

What you should do as an undergrad

As an undergrad, you should find ways to get broad experience in 2 or 3 areas that you're interested in. Professors (or their PhD students) are always on the lookout for volunteers, and would be happy to have an extra pair of hands on board. I volunteered at an academic lab and also fulfilled my internship requirement with a startup doing their own R&D.

It'd be best if you could aim to get your name on a published paper as well, ideally first author - this is a strong signal for doing well in a PhD. Helping out in a lab can get your name on a paper, since you'll be helping with the data collection and possibly editing of the paper. It also gives you a good idea of how the entire process of research will go.

When you're just starting out...

In most places as a researcher, your KPI will be data, results, and papers. So there is a balance between quality and quantity, and sometimes quantity will have to win (and also because you're just really done with the research at that point, or out of funding).

At the start, it's difficult for you to come up with good research ideas. A lot of the time, you'll be following directions without really knowing why you do it. In short, you're just a lab data producer. I spent a lot of time asking my mentors questions to really grasp the science behind it all. This is good for developing the lab skills that you will need later. I suspect this will be true even for a PhD, but a PhD entails more thinking and reading up and finding new methods for experiments.

Looking for a PhD would also be like looking for a job - it depends on the specific professors you'd like to work under and whether they have space in that specific lab. It won't be as organised as applications for undergraduate study.

Research in Industry vs Academia

In industry, you may not need to write papers or submit to journals, and you don't have to teach. You can spend more time on literature review and carrying out experiments (or asking juniors to do them for you). However, the research would be more applied and based on business needs. There is also more pressure to provide results, since they will directly inform product development. Eventually you'll probably end up managing a team of scientists, and possibly become CTO of a company in your field.

In academia, you'll have more research freedom (in maybe 5-10 years after your PhD and your postdoc and becoming a professor). And then you'll end up writing grants about half the time. So there's very little time to do 'actual' research, and the people closer to the ground - your PhD students - will be clearer on what's state of the art. Eventually you'll be managing a team of PhD students, and be like a CEO of the lab. Also, you'll have a teaching load in most places, which reduces the time you have on actual research. However, you have more resources - university labs tend to be quite decked out.

The Long Slog of Publishing

Being able to write - and enjoy writing - helps, since that is what a research paper is at its core.

You'll need to submit your paper over and over, before things get published - the timeline for the papers I have so far are months to years before things get published, due to the back-and-forth between you and the editor. There's no formal process, so you can often just email different journals to see if they'll take it. Kind of like a job application, but for your paper.

Academia is just another industry

So, usual office politics still apply - you need to please your boss/supervising professor. They are also tied by grant money and what the 'customer' wants - if you're in industry it'll be improving your product based on what your customer wants. If you're in academia it'll be trying to convince people to give you grants, or in Singapore, largely influenced by what the government wants R&D to be.

So, do I still want to do research?

At this point I'm not so sure anymore. Towards the end of my undergraduate years, I started to think that maybe the bottleneck for the issues I care about was not technology altogether. And if that's true, why should I still try to develop technology?

I'm still keeping a PhD in view, and may choose to pursue it a little bit further down the road. Four more years - and even longer after that - is a long time, and I want to consider it carefully. From my experiences I think I might also not have the best personal fit, either. I'm more of a sprinter than a marathoner, and I'm not sure if I'm willing to endure the downsides for the potential upsides.

I also see lab as a necessary evil, instead of something I enjoy. I know some of my friends enjoy the process of making samples and testing them out, and I think that would make a difference on the personal fit side.

Learn more

80,000 Hours has a good article that covers the academic research path.

Richard Hamming's talk - You and Your Research is also a nice piece to read.

A Quora ask on what a good PhD student would look like.